Project.

Ontology defines an object as a substantial individual endowed with all its substantial properties, in particular the property of change.

Indeed, through the use of objects a change occurs in them known as “object memory”. This slow process of acquiring memory is fundamental, since it ultimately means that an object ends up being trash or becomes a unique personal treasure.

But this memory, although very powerful, is also very fragile. If at the moment when an object changes hands its memory is not transferred to the new owner, it is lost, leaving the object again in danger of becoming trash.

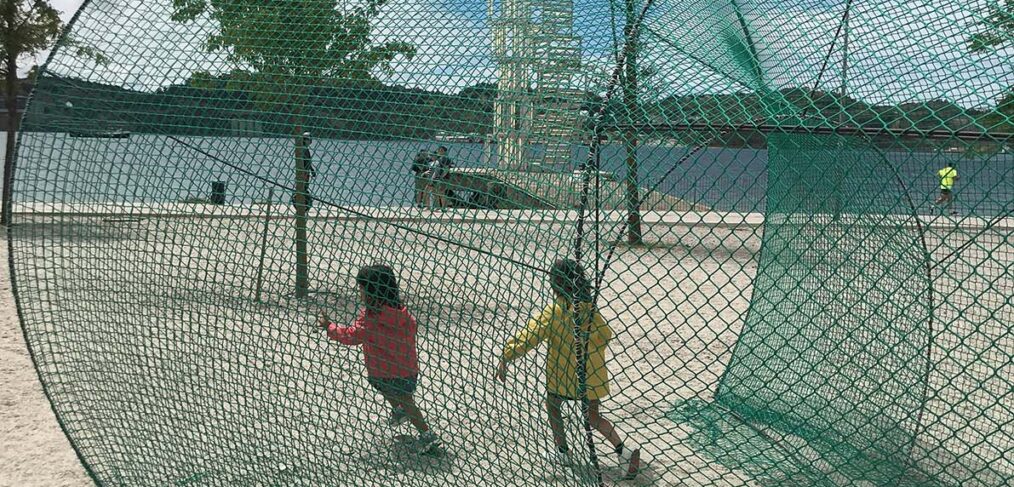

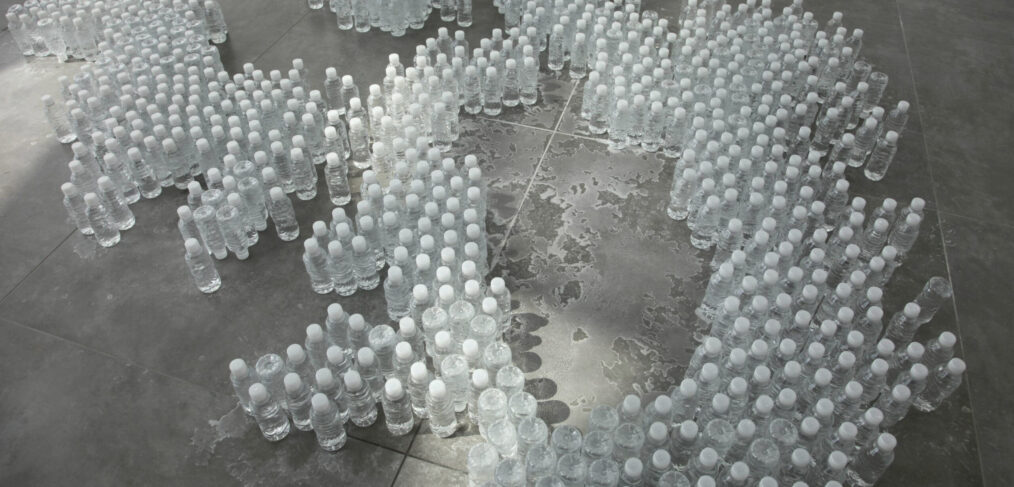

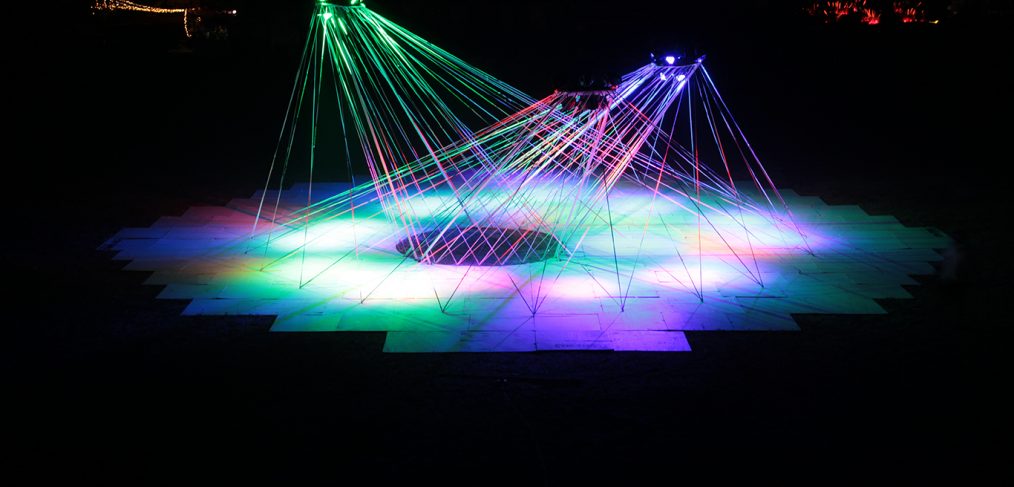

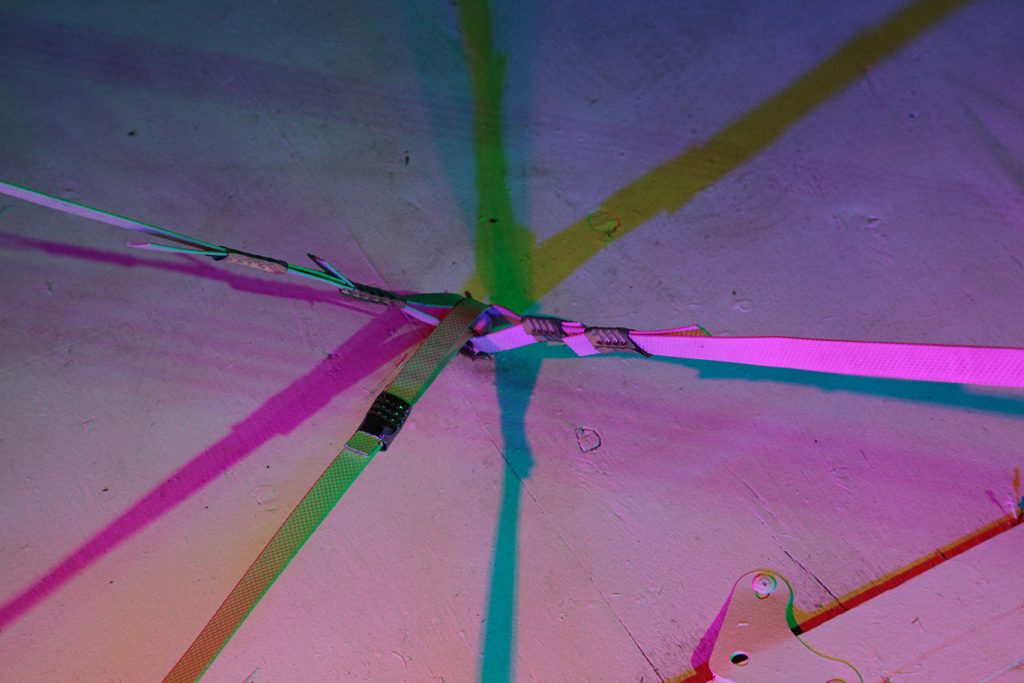

In an experiment never carried out before, this installation attempted to produce a transfer of memory from a series of objects from the collection of the Museu de la Vida Rural to some random plastics from the greenhouses in the area. The latest theories suggest that this process, although slow and complex, could be possible.

For the transfer to be effective, people must move through containers specifically designed for this purpose, observing the rural objects through the plastic surfaces. It is in this act of observation that the transfer could occur successfully.

The rural objects that were part of this experiment belonged to people who used them for work, household chores, travel and generally, to have a better life. Many were handmade and some had to be repaired numerous times to continue to be useful. On all of them, scratches, signs of use and the passage of time could easily be observed.

Plastic, however, is very resistant to memory. The polymer chains that compose it prevent memories from easily penetrating its structure and, thanks to its high molecular weight, sweat, dirt, words and other substances that carry memories can easily be removed from its surface.

With this experiment we wanted to see if technological evolution is this, that objects spend less time with us so that they cannot acquire a memory that prevents us from replacing them with new ones.

Context.

This installation was part of the exhibition Plàstic, organized by the Museu de la Vida Rural and curated by Núria Vila.

Faced with the challenge of dealing with a topic and a material outside the museum’s permanent collection, we wanted to investigate the possible connections between both worlds, because beyond the romantic vision that we may have of life in villages, the contemporary reality is that plastics are as much a part of the rural life model as any other object.

The visit to the museum’s warehouses, where numerous objects donated by people from the area accumulate, prompted us to try to understand why some objects can belong to us for decades and pass from generation to generation and others last in our hands for less than a few minutes.